Environmental photographers position themselves at the intersection of art and activism, wielding their cameras as tools for documenting planetary change. Unlike traditional nature photography that celebrates beauty for its own sake, this specialty demands a narrative conscience—every frame carries the weight of ecological truth, whether revealing the majesty worth preserving or the devastation we can no longer ignore.

The distinction matters more than semantics suggest. While a nature photographer might capture a pristine waterfall at golden hour, an environmental photographer considers the watershed’s broader story: upstream deforestation, downstream pollution, or the communities depending on that water source. This contextual awareness transforms individual images into chapters of larger environmental narratives that can influence policy, shift public perception, and drive conservation action.

This field requires both technical mastery and journalistic integrity. You’ll need to understand how wide-angle lenses can emphasize scale when documenting glacier retreat, why telephoto compression helps juxtapose industrial development against wilderness, and how long exposures can reveal pollution patterns invisible to the naked eye. But gear knowledge alone won’t distinguish your work—you must also develop research skills to identify stories worth telling, build trust with scientists and communities, and navigate the ethical considerations inherent in representing environmental issues visually.

Whether you’re photographing coral bleaching, renewable energy installations, or indigenous land stewardship, your role extends beyond observer to visual storyteller and witness. The images you create today become tomorrow’s historical record, evidence in environmental debates, and catalysts for the changes our planet desperately needs.

What Defines an Environmental Photographer

The Documentary Approach vs. The Artistic Vision

Environmental photographers walk a fascinating tightrope between two worlds. On one side, there’s the documentary mandate—capturing truthful, unmanipulated evidence of environmental conditions. On the other, there’s the need to create images powerful enough to make viewers stop scrolling and actually care.

Unlike traditional documentary photography approaches that prioritize pure observation, environmental photography demands emotional resonance. You’re not just recording what’s happening to a coral reef or forest—you’re making people feel its loss or potential.

This balance requires strategic choices. Consider James Balog’s glacier documentation: his time-lapse sequences are scientifically accurate yet cinematically stunning. He didn’t manipulate the glaciers’ retreat, but he carefully chose angles, lighting conditions, and composition to amplify the visual drama of climate change.

The key is maintaining journalistic ethics while exercising creative control over elements like timing, perspective, and context. You might wait hours for the perfect light to illuminate a polluted waterway, but you won’t digitally add trash that isn’t there. You’ll frame a clear-cut forest against intact wilderness to emphasize contrast, but you won’t misrepresent the actual scale of destruction.

Think of it this way: your artistic vision is the delivery system for documentary truth. The composition draws viewers in; the authenticity keeps them engaged and drives action.

Ethics and Responsibility in the Field

Environmental photography carries profound ethical responsibilities that extend far beyond simply capturing a beautiful image. Your presence in natural spaces can impact wildlife behavior, vegetation, and delicate ecosystems, so practicing minimal-impact techniques is essential. This means staying on designated trails, maintaining safe distances from wildlife, and never disturbing nests, dens, or sensitive habitats for a better shot.

Honest representation stands as another cornerstone of ethical environmental work. While post-processing is standard practice, there’s a critical difference between enhancing an image and fundamentally misrepresenting reality. Adding dramatic skies from different locations, removing inconvenient elements like power lines when documenting actual conditions, or exaggerating colors to the point of fantasy can mislead viewers about environmental realities. When your work aims to inform or advocate, accuracy matters deeply.

Similar to ethical documentation practices in cultural photography, environmental work requires respecting your subjects—whether that’s a threatened species or a fragile landscape. Consider the long-term consequences of sharing location data that might attract crowds to vulnerable areas. Sometimes the most responsible action is keeping specific locations private while still sharing the broader environmental message your images convey.

The Technical Arsenal: Gear That Tells Environmental Stories

Camera Bodies Built for Harsh Conditions

Environmental photography demands cameras that can withstand punishment. When you’re documenting deforestation in tropical humidity, photographing coastal erosion in salt spray, or capturing Arctic wildlife in subzero temperatures, your gear becomes a critical factor in whether you get the shot—or head home empty-handed.

Weather-sealing is non-negotiable for serious environmental work. Look for cameras with proper gaskets around buttons, doors, and mounting points. The Canon EOS R5 ($3,900) and Nikon Z8 ($4,000) offer exceptional weather resistance and have proven themselves in brutal conditions. For photographers on tighter budgets, the Olympus OM-1 ($2,200) punches well above its weight class with impressive sealing and a smaller, more portable form factor—a real advantage when hiking to remote locations.

Sensor size matters, but perhaps not how you’d expect. Full-frame sensors excel in low light and offer superior dynamic range for capturing detail in both shadows and highlights—essential when documenting everything from dark forest canopies to bright glacial landscapes. However, Micro Four Thirds systems provide excellent image quality while reducing pack weight, a trade-off worth considering for backcountry work.

Durability extends beyond weather-sealing. Magnesium alloy bodies handle drops better than plastic, and cameras with integrated vertical grips distribute weight more comfortably during long shooting days. The Sony A1 ($6,500) represents the premium end, while the Nikon Z6 III ($2,500) delivers professional reliability at a more accessible price point. Consider buying used or refurbished bodies to stretch your budget further—these cameras are built to last.

Lenses That Capture Context and Detail

Your lens choice fundamentally shapes how viewers understand environmental stories. Wide-angle lenses (14-35mm) excel at establishing context—capturing vast landscapes affected by climate change or showing the relationship between human development and natural habitats. When documenting deforestation, a 24mm lens can simultaneously show cleared land in the foreground and remaining forest stretching toward the horizon, creating immediate visual impact that statistics alone can’t achieve.

Mid-range zooms (24-70mm or 24-105mm) offer versatility for documenting human-environment interactions. These lenses work beautifully for portraits of environmental activists in their settings or capturing researchers at work, maintaining intimacy while preserving environmental context.

Telephoto lenses (100-400mm or longer) become essential when documenting wildlife affected by environmental changes—think polar bears on diminishing ice floes or birds nesting near industrial sites. The compression effect of longer focal lengths can emphasize proximity between wildlife and human encroachment, strengthening your narrative without disturbing sensitive subjects.

The key is intentionality. A wide-angle shot of a polluted river tells a different story than a telephoto close-up of contaminated water. Understanding how focal length shapes perspective allows you to craft more compelling environmental narratives that resonate with viewers and inspire action.

Essential Accessories for Extended Field Work

Extended field work demands equipment that keeps you operational when you’re far from civilization. **Drones** have revolutionized environmental photography by providing aerial perspectives that reveal landscape patterns, deforestation impacts, and ecosystem relationships invisible from ground level. Entry-level models like the DJI Mini series work well for beginners, while professionals often choose the Mavic 3 for superior image quality and flight time.

**Time-lapse equipment**—including intervalometers and motion control sliders—documents environmental changes over hours, days, or seasons. A sturdy tripod paired with an intervalometer lets you capture glacier movement, tide cycles, or weather pattern shifts that tell compelling stories about environmental dynamics.

Don’t overlook **protective gear**: weather-sealed camera bags, lens rain covers, and silica gel packets protect your investment in humid rainforests or dusty deserts. I’ve learned this lesson the hard way during monsoon season shoots.

Finally, **portable power solutions** like high-capacity battery banks and solar chargers keep cameras, drones, and laptops running during multi-day expeditions. Calculate your daily power consumption beforehand—running out of juice when documenting a crucial environmental event is a photographer’s nightmare you’ll want to avoid.

Visual Techniques for Showing Change Over Time

The Power of Repeat Photography

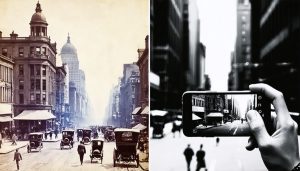

One of environmental photography’s most compelling techniques involves returning to the exact same spot repeatedly—sometimes over months, sometimes over decades—to document change. This method, called repeat photography or “rephotography,” transforms your camera into a time machine, revealing environmental shifts that might otherwise go unnoticed in our day-to-day lives.

The concept is beautifully simple: photograph a location, then return periodically to capture it again from the identical vantage point. The results can be startling. Glaciers that once filled entire valleys shrink to mere patches of ice. Forests disappear, replaced by farmland or development. Coastlines erode. Cities expand outward like spreading ink stains.

To make this technique work effectively, precision matters more than expensive gear. Start by marking your exact shooting location using GPS coordinates—most smartphones can record these with remarkable accuracy. Take reference photos of your immediate surroundings, including distinguishing landmarks or ground features that will help you relocate the spot years later. Some photographers even leave physical markers like small cairns or drill discrete holes for tripod legs.

Consistency in composition is equally crucial. Use the same focal length for each revisit, and align key elements—a distinctive tree, rock formation, or building—in identical positions within your frame. Many photographers create detailed field notes sketching the scene’s layout and recording camera settings, time of day, and season.

The patience this approach demands is considerable, but the storytelling power is unmatched. Your images become irrefutable evidence of environmental change.

Capturing Scale and Context

Environmental issues often exist on scales difficult for viewers to grasp—a melting glacier, a sprawling landfill, or endless rows of industrial agriculture. Your job as an environmental photographer is to make that scale tangible through thoughtful composition.

Including human elements in your frame serves as an instant reference point. A single person standing before a towering wall of plastic waste or walking through a deforested landscape transforms abstract concepts into relatable scenes. This technique isn’t just about showing size—it creates empathy by placing viewers in the frame alongside your subject.

Aerial perspectives offer another powerful tool for conveying magnitude. Whether shooting from drones, aircraft, or elevated vantage points, the bird’s-eye view reveals patterns invisible from ground level. Deforestation boundaries, agricultural runoff spreading through waterways, or the geometric sprawl of urban development all become strikingly apparent from above. These perspectives provide context that ground-level photography simply cannot achieve.

Juxtaposition creates immediate visual tension that demands attention. Frame pristine wilderness against industrial development, traditional farming methods beside corporate operations, or thriving ecosystems next to degraded ones. This side-by-side comparison doesn’t require lengthy captions—the contrast speaks for itself.

When composing these shots, consider using wide-angle lenses to emphasize vastness, or telephoto lenses to compress space and highlight contrasts. Remember that your compositional choices directly influence how viewers understand the environmental story you’re documenting. Make every framing decision count toward building that narrative impact.

Building Compelling Environmental Narratives

From Single Images to Photo Essays

A single powerful image can grab attention, but a photo essay holds it—and that’s where environmental photographers truly shine. Think of individual photos as sentences and your photo essay as a complete story with beginning, middle, and end.

Start by identifying your **anchor image**—the photograph that best encapsulates your entire message. This isn’t necessarily your most dramatic shot, but rather the one that best represents your theme. If you’re documenting coastal erosion, your anchor might show a house teetering on a crumbling cliff edge, immediately communicating the story’s stakes.

Next, establish your narrative flow. A strong photo essay typically includes establishing shots that set the scene, detail images that reveal intimate aspects, and environmental portraits that add human connection. For a story about urban heat islands, you might open with an aerial view of concrete sprawl, move to close-ups of cracked pavement and struggling vegetation, then include portraits of residents seeking relief.

**Theme consistency** is crucial. Your editing style, color palette, and compositional approach should feel cohesive throughout the series. If you’re working with moody, desaturated tones in your opening images, maintain that aesthetic to avoid jarring viewers.

Aim for 8-12 images in a complete essay—enough to explore your subject thoroughly without overwhelming your audience. Each photograph should advance the narrative, not merely repeat what came before. Consider pacing too: alternate between wide and tight shots, action and stillness, to create visual rhythm that keeps viewers engaged through your environmental story.

Working With Communities and Subjects

Environmental photography often intersects with human stories, requiring thoughtful engagement with the communities most affected by ecological change. Before photographing people in environmental contexts, establish genuine relationships and understand their perspectives. This means spending time listening, learning about their connection to the land, and ensuring your presence serves their interests alongside your creative goals.

Obtaining informed consent goes beyond a quick signature. Explain how images will be used, where they’ll appear, and what narrative they’ll support. Share your work with subjects afterward when possible, and honor any restrictions they request. Remember that working with communities requires cultural sensitivity, particularly when documenting Indigenous peoples or vulnerable populations.

Represent people with dignity, avoiding “poverty porn” or stereotypical portrayals that strip away agency. Show resilience alongside struggle, and context alongside challenge. Your subjects aren’t props to illustrate environmental degradation—they’re collaborators in telling a larger story.

Consider collaborating directly with community members who can guide your understanding and access. Some successful environmental photographers work with local fixers or partner organizations, ensuring authentic representation while compensating communities fairly for their time and knowledge.

Real-World Projects and What We Can Learn From Them

Studying successful environmental photography projects reveals the powerful intersection of technical skill, narrative vision, and advocacy. Let’s examine several groundbreaking projects that have shaped how we communicate environmental stories through images.

**James Balog’s “Chasing Ice” (2007-present)** remains one of the most technically ambitious environmental photography projects ever undertaken. Balog installed time-lapse cameras across the Arctic to document glacial retreat over multiple years. His technical approach was revolutionary—he designed weatherproof camera systems that could withstand extreme conditions while capturing consistent images every daylight hour. The narrative strategy proved equally important: by condensing years of change into seconds of video, Balog made the abstract concept of climate change viscerally immediate. What we learn here is that patience and systematic documentation can reveal changes invisible to casual observation. His project demonstrates how technical innovation serves storytelling—the time-lapse technology wasn’t just a gimmick; it was the only way to make glacial movement comprehensible to human perception.

**Sebastião Salgado’s “Genesis” (2004-2013)** took a different approach, using large-format black and white photography to document pristine landscapes and indigenous communities. Salgado’s technical choices—shooting exclusively in monochrome with medium and large format cameras—stripped away color’s distractions to emphasize form, texture, and the essential relationship between humanity and environment. His narrative strategy focuses on what remains unspoiled rather than what’s been destroyed, creating a sense of what’s at stake. The lesson? Sometimes showing beauty is more powerful than documenting destruction. His methodical approach, spending weeks or months in single locations, reminds us that meaningful environmental photography demands deep engagement rather than superficial coverage.

**Chris Jordan’s “Midway: Message from the Gyre” (2009-2011)** documented albatross chicks on Midway Atoll who died after being fed plastic debris by their parents. Jordan’s technical approach was straightforward—detailed, respectful documentation using natural light—but his narrative strategy proved devastating in its simplicity. By photographing the decomposed birds with their stomachs full of recognizable plastic objects, he created an undeniable visual argument about ocean pollution. This project teaches us that sometimes the subject itself carries such power that technical restraint serves the story better than artistic flourishes.

Contemporary photographers like Paul Nicklen and Cristina Mittermeier leverage Instagram’s platform to combine stunning imagery with immediate environmental messaging, demonstrating how digital platforms can amplify conservation photography’s reach beyond traditional galleries and publications.

Getting Started as an Environmental Photographer

Breaking into environmental photography doesn’t require exotic travel or expensive assignments—it starts in your own backyard. Begin by documenting local environmental issues: a polluted stream, urban development encroaching on green spaces, or community gardens thriving in unexpected places. These nearby stories let you develop your voice and technical skills while building a portfolio that demonstrates your commitment to environmental storytelling.

Your portfolio should showcase your ability to balance aesthetic impact with narrative clarity. Include 10-15 strong images that tell complete stories, not just beautiful scenes. Pair each project with concise captions explaining the environmental context and what drew you to the subject. This approach proves to editors and organizations that you understand both the visual and journalistic aspects of the work.

Start connecting with local environmental nonprofits and conservation groups. Many smaller organizations need quality imagery but lack photography budgets, making them perfect partners for early projects. Offer to document their restoration efforts or community programs in exchange for portfolio pieces and real-world experience. These relationships often lead to paid assignments as your reputation grows.

For publications, research outlets that regularly feature environmental content—from regional magazines to online platforms like bioGraphic or Mongabay. Study their visual style and pitch specific stories rather than generic portfolios. Demonstrate you’ve done your homework by understanding their audience and editorial needs.

The reality is that most environmental photographers balance passion projects with commercial work. Wedding photography, corporate assignments, or stock photography can fund your environmental pursuits while you build recognition. Set realistic goals: perhaps dedicate one project per quarter to environmental work while maintaining income through other photography services. This sustainable approach prevents burnout and keeps your environmental work authentic rather than financially desperate.

Remember, every established environmental photographer started locally. Your unique perspective on your community’s environmental challenges is valuable—no one else sees those stories through your lens.

We’ve never needed environmental photographers more urgently than we do right now. As climate change accelerates and ecosystems face unprecedented pressures, visual storytelling has become one of our most powerful tools for creating awareness and inspiring action. The images you capture—whether documenting a threatened wetland in your neighborhood or chronicling the effects of rising temperatures on distant glaciers—contribute to a vital global conversation about our planet’s future.

Here’s what makes this moment particularly important: environmental narratives desperately need diverse voices. Not every story requires exotic locations or specialized wildlife equipment. Your local creek, the urban green space facing development, or the community garden fighting pollution—these stories matter just as much as dramatic wilderness scenes. Professional photographers bring technical expertise and reach, but hobbyists and enthusiasts offer something equally valuable: authentic connections to places and communities that larger outlets often overlook.

If you’re drawn to environmental photography, start where you are. Practice telling visual stories about the environment you know best. Experiment with different techniques, study how light and composition can evoke emotion, and think critically about the narratives your images create. Share your work through local organizations, social media platforms, or community groups where it can make tangible impact.

Looking ahead, photography’s role in environmental advocacy will only grow more sophisticated and essential. As technology evolves and new platforms emerge, the demand for compelling, honest environmental imagery will expand, creating opportunities for photographers at every level to contribute meaningfully to this crucial field.