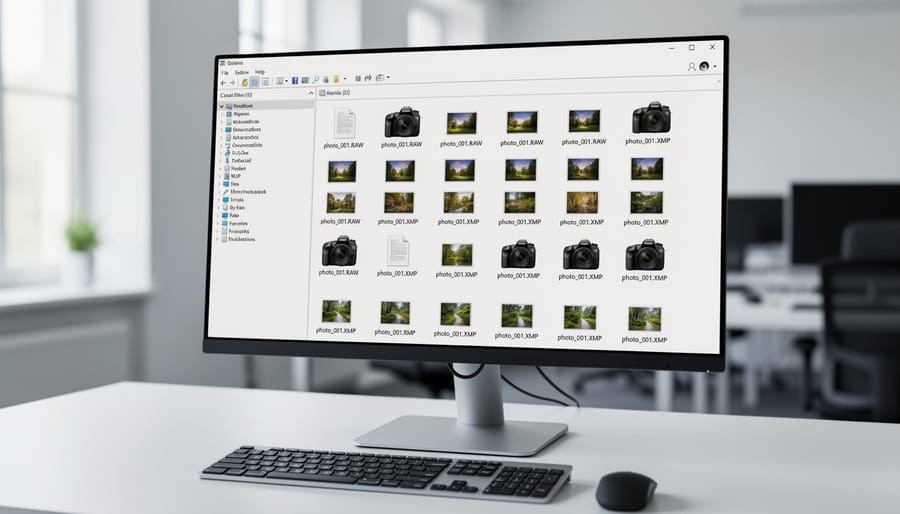

You’ve just imported your photos and noticed unfamiliar XMP or XML files sitting next to your RAW images—these are sidecar files, and understanding them could save you hours of lost editing work.

Sidecar files are separate text documents that store all your editing instructions, metadata, and adjustments without touching your original image file. When you adjust exposure in Lightroom, add keywords, or apply color corrections, programs like Adobe Camera Raw, Capture One, and Photo Mechanic save these changes to a sidecar rather than embedding them into your RAW file. Think of them as instruction manuals that tell your software exactly how to display your image, while your original RAW file remains pristine and untouched.

This separation creates both powerful flexibility and potential headaches. The advantage is clear: your original capture stays intact, allowing you to experiment fearlessly and revert to the starting point anytime. You can also transfer your edits between computers simply by moving both files together. However, this two-file system means trouble if you accidentally delete a sidecar, move only one file to another location, or back up your photos without including these companion files.

For photographers managing thousands of images across multiple devices, sidecar files represent both your editing history and your vulnerability. One misplaced file can mean hours of adjustments vanished instantly. Understanding how these files work—and developing habits to protect them—transforms file management from mysterious frustration into confident control over your photographic workflow.

What Are Sidecar Files and Why They Matter

The Problem RAW Files Present

RAW files are essentially digital negatives—proprietary formats unique to each camera manufacturer that contain pure sensor data. Think of them like a sealed film canister: once developed and packaged, you wouldn’t want to reopen and fiddle with the contents, as that would damage the original. The same principle applies to RAW files.

When you edit a RAW file in software like Lightroom or Capture One, the program doesn’t actually modify the original file. Here’s why: RAW files use proprietary structures that aren’t designed to accommodate additional data. If editing software tried to write your adjustments—exposure changes, color corrections, crop information—directly into the RAW file, it would risk corrupting the precious sensor data or making the file unreadable.

Imagine trying to write notes in the margins of a sealed package. You’d either damage the wrapper or be unable to add the information at all. Additionally, different editing programs would need to understand each camera manufacturer’s unique RAW format, then somehow agree on where and how to store edit data without conflicts. A file edited in Lightroom might become incompatible with Capture One, or worse, completely unusable.

This fundamental limitation means your edits need to live somewhere else entirely—which is exactly where sidecar files enter the picture.

What Lives Inside a Sidecar File

Think of a sidecar file as your digital darkroom notebook—it records every creative decision you make without touching the original photograph. When you open a RAW file in Adobe Lightroom, Capture One, or similar editing software, the sidecar file begins documenting your work the moment you make that first adjustment.

The most common data stored includes exposure compensation (like that +0.7 stop you added to brighten your subject’s face), white balance shifts (remember correcting that overly warm sunset?), and contrast adjustments. Your entire develop history lives here—shadows lifted, highlights recovered, clarity added to bring out texture in landscape details.

Beyond basic adjustments, sidecar files store organizational elements that are crucial for metadata management. This includes star ratings for separating keepers from rejects, color labels (those red, yellow, and green tags you use during culling), and keywords you’ve assigned for searching later. If you’ve ever tagged photos with “wedding,” “sunset,” or “client Smith,” that information lives in the sidecar.

Geometric corrections also find their home here—crop dimensions, aspect ratio changes, straightening adjustments, and lens distortion corrections. Even local adjustments like graduated filters, radial filters, and adjustment brushes are meticulously recorded, storing exactly where you applied that dodge to brighten eyes or that burn to darken distracting background elements.

Essentially, sidecar files contain everything except the pixel data itself—they’re pure instruction sets telling software how to display your creative vision.

Common Sidecar File Formats You’ll Encounter

XMP Files: The Universal Standard

When it comes to sidecar files, Adobe’s XMP format has emerged as the clear winner in the photography world. XMP stands for Extensible Metadata Platform, and while the technical name might sound intimidating, think of it as a universal language that different photo editing programs can all understand and speak.

Adobe introduced XMP in the early 2000s as an open standard, meaning other software developers could freely adopt it. This openness proved crucial to its success. Today, XMP files are the default sidecar format for industry heavyweights like Adobe Lightroom, Adobe Camera Raw, and Photoshop. But the adoption extends far beyond Adobe’s ecosystem. Capture One, ON1 Photo RAW, ACDSee, and numerous other professional editing applications all support XMP sidecar files.

Why has XMP become the industry standard? The answer lies in its flexibility and reliability. XMP files store everything from basic exposure adjustments and color corrections to complex local adjustments, keywords, ratings, and copyright information. Because the format is text-based and uses XML structure, it’s both human-readable and incredibly robust. If you open an XMP file in a basic text editor, you’ll actually see your editing instructions laid out in organized code.

For photographers, this widespread adoption means you’re not locked into a single software ecosystem. You can start editing in Lightroom, switch to Capture One, and your basic adjustments will transfer seamlessly. This interoperability gives you freedom and protects your investment in time spent organizing and editing your photo library.

Proprietary Sidecar Formats

While XMP has become the de facto standard, camera manufacturers and software developers have created their own proprietary sidecar formats over the years. These specialized formats can offer enhanced features but come with compatibility trade-offs worth understanding.

Canon’s .CR3 files, for instance, sometimes generate .CRM sidecars that store metadata specific to Canon’s Digital Photo Professional software. Similarly, some Nikon software creates .NXL sidecars for .NEF RAW files, containing edits made in Nikon’s proprietary editing tools. The challenge? These sidecars typically only work within their native ecosystems. If you edit a Canon RAW file in DPP and generate a .CRM sidecar, then later switch to Lightroom, those edits won’t transfer—Lightroom creates its own XMP sidecar instead.

Software-specific formats present similar limitations. Phase One’s Capture One uses .COS sidecars, while DxO PhotoLab generates .DOP files. Each stores edits in proprietary structures that other programs simply can’t read.

Here’s a real-world scenario: imagine you’ve spent hours perfecting adjustments in Capture One, only to have a client request files compatible with their Lightroom workflow. Your .COS sidecars won’t help—you’ll need to export adjusted images or start fresh.

The practical takeaway? If you work across multiple platforms or collaborate with others, standardized XMP sidecars offer better flexibility. Proprietary formats shine when you’re committed to a single ecosystem and want access to manufacturer-specific features. Just remember that choosing proprietary sidecars means accepting potential migration headaches down the road if you ever switch software or share files with users on different platforms.

Catalog Files vs. Sidecar Files

Understanding how different software handles metadata can save you from workflow headaches down the road. Some programs, like Adobe Lightroom Classic, store your edits and adjustments in a central catalog database rather than creating individual sidecar files for each image. This catalog approach keeps everything tidy in one place, but it also means your edits aren’t automatically traveling with your image files if you move them to another computer or share them with a colleague.

Other applications, including Adobe Camera Raw, Capture One, and Darktable, rely primarily on XMP sidecar files. These programs create a separate file for each RAW image, keeping the metadata right alongside the original. The advantage? Your edits are portable and self-contained. The potential downside? You’ll have twice as many files to manage in your folders.

Lightroom Classic offers a hybrid approach through its “Automatically write changes into XMP” preference. Enabling this option tells Lightroom to create XMP sidecar files alongside its catalog, giving you the best of both worlds—the convenience of catalog organization plus the portability of sidecar files. This setting becomes particularly valuable when collaborating with others or archiving projects for long-term storage.

How Different Software Handles Sidecar Files

Adobe Lightroom and Photoshop

Adobe has pioneered the use of XMP sidecar files, making them central to how Lightroom Classic and Camera Raw handle non-destructive editing. When you import RAW files into Lightroom, the software stores your adjustments in its catalog database by default. However, you can configure Lightroom to automatically write these edits to XMP sidecar files, ensuring your work exists independently of the catalog.

To enable automatic XMP creation in Lightroom Classic, navigate to Catalog Settings, select the Metadata tab, and check “Automatically write changes into XMP.” This setting tells Lightroom to create or update sidecar files whenever you make edits, providing an extra safety net for your work. Without this enabled, you’ll need to manually save metadata by selecting photos and pressing Command+S (Mac) or Control+S (Windows).

Bridge and Camera Raw always use XMP files, creating them immediately when you make adjustments. These sidecar files sit alongside your RAW files with matching names but an .xmp extension. For Photoshop users working with Camera Raw, these files automatically preserve your RAW processing settings.

This approach integrates seamlessly with other editing workflow tools, allowing you to switch between Adobe applications while maintaining complete edit history. Always back up both your original files and their XMP companions to prevent losing hours of careful adjustments.

Capture One, DxO, and Other Third-Party Software

While Adobe dominates the conversation around sidecar files, other RAW processing applications take different approaches that can impact your workflow. Capture One, for instance, creates its own proprietary .COS or .COV sidecar files containing session-specific edits and adjustments. These sidecars work beautifully within Capture One’s ecosystem but won’t communicate with Lightroom or other software.

DxO PhotoLab follows a similar path, generating .DOP sidecar files that store lens corrections, noise reduction settings, and other DxO-specific adjustments. ON1 Photo RAW and Luminar also create their own sidecar formats, each speaking its own language.

Here’s the practical challenge: when you switch between programs, your edits don’t transfer. If you’ve spent hours perfecting an image in Capture One and later open it in Lightroom, you’ll see the original RAW file with zero adjustments applied. The programs simply can’t read each other’s sidecars.

The XMP standard was supposed to solve this compatibility issue, and some software does support XMP sidecars for basic metadata like keywords and ratings. However, program-specific adjustments like tone curves or color grading typically remain locked within their native format. When working across multiple applications, consider establishing a primary editing program and using others only for specialized tasks, ensuring you maintain a clear master copy of your work.

Camera Manufacturer Software

Major camera manufacturers each have their own free editing software, and each handles sidecar files differently—sometimes in ways that can surprise you. Canon’s Digital Photo Professional (DPP) stores all editing data in a proprietary database rather than creating individual sidecar files. This means your adjustments live in a central location on your computer, which keeps your image folders tidy but creates a potential vulnerability: if that database becomes corrupted or you’re working on a different computer, your edits aren’t traveling with your images.

Nikon’s NX Studio takes a hybrid approach. By default, it saves adjustments to its own database, but you can configure it to create XMP sidecar files, giving you more flexibility for cross-platform workflows. This option is tucked away in the preferences, so many users don’t realize it exists.

Sony’s Imaging Edge suite similarly relies on a centralized database system. While this creates a streamlined experience within Sony’s ecosystem, it means your editing data isn’t portable in the same way that XMP sidecars would be.

The practical takeaway? If you’re using manufacturer software exclusively and staying within one computer system, their database approach works fine. However, if you plan to switch editing applications later or work across multiple machines, you’ll want to export your images as TIFFs or JPEGs to preserve your edits, since those adjustments won’t transfer to other programs through standard sidecar files.

Best Practices for Sidecar File Management

Keeping RAW and Sidecar Files Together

The golden rule for sidecar files is simple: they must stay with their parent RAW file at all times. When you move, rename, or copy a RAW file, its sidecar needs to move with it. Otherwise, you’ll lose all your editing work.

Start with a solid folder structure. Keep RAW files and their sidecars in the same folder—never separate them into different locations. Many photographers organize by date and project, like “2024/2024-03-15_Wedding_Smith” which makes batch operations easier and reduces the risk of separating files.

Naming conventions are your safety net. When renaming files, use software that automatically renames both the RAW and sidecar together. Adobe Bridge and Photo Mechanic handle this seamlessly. If you rename manually, update both files identically—if your RAW is “IMG_5432.CR3” and you rename it to “Sunset_Beach_01.CR3,” the sidecar must become “Sunset_Beach_01.xmp.”

During file transfers, always select both files. Enable “show file extensions” in your operating system so you can visually confirm the pair before moving them. When backing up your images, following photo storage best practices means ensuring your backup software captures both file types—some backup programs need configuration to include sidecar files alongside image files.

Backup Strategies That Actually Work

The single biggest mistake photographers make is backing up their RAW files while forgetting the sidecars entirely. Here’s the reality: if your XMP or sidecar file disappears, so do all your edits. Your meticulously crafted adjustments vanish, leaving you with the original RAW file as if you’d never touched it.

To protect your work, treat sidecars and RAW files as inseparable pairs. When implementing a comprehensive backup strategy, ensure your backup software doesn’t filter out these small files. Many photographers discover too late that their cloud backup service excluded XMP files because they seemed insignificant.

Create multiple backup copies on different drives, and verify that both file types transferred successfully. If you’re moving files between computers or external drives, always use copy-and-paste rather than cut-and-paste to maintain an original until you’ve confirmed everything transferred correctly.

For recovery, if you’ve lost a sidecar but still have your catalog file (like Lightroom’s LRCAT file), you can often regenerate the XMP by selecting the image and choosing “Save Metadata to File” from the metadata menu. This recreates the sidecar based on your catalog’s current state, though this only works if your catalog itself survived intact.

Software Settings to Enable Now

Enabling sidecar files is simpler than you might think, and doing it now can save you headaches down the road. Let’s walk through the settings in the most popular editing applications.

In Adobe Lightroom Classic, sidecar files are actually enabled by default for RAW images, which is great news. Lightroom automatically creates XMP sidecar files whenever you make adjustments to RAW photos. However, if you want to ensure your settings are writing metadata to these files, navigate to Catalog Settings (found under Edit on Windows or Lightroom Classic on Mac). Click the Metadata tab and check the box that says “Automatically write changes into XMP.” This ensures your edits are written to sidecar files immediately rather than staying locked in Lightroom’s catalog.

For Capture One users, head to Preferences, then select the Image tab. Look for the section labeled “Save adjustments” and choose “Sidecar files” from the dropdown menu. This tells Capture One to write all your edits to XMP files instead of keeping everything in its catalog database.

Adobe Camera Raw users working in Bridge or Photoshop should open Camera Raw preferences (click the three horizontal lines in Camera Raw’s interface, then select Preferences). Under the File Handling tab, ensure “Sidecar ‘.xmp’ files” is selected in the “Save image settings in” section.

Once configured, these applications will automatically generate and update sidecar files as you work. You won’t need to manually export or save anything special—the software handles it behind the scenes, giving you peace of mind that your creative work is preserved independently from any single catalog or database.

Troubleshooting Common Sidecar File Issues

When Your Edits Disappear

Nothing’s more frustrating than opening an image you spent hours perfecting only to find it’s reverted to the completely unedited RAW file. Before you panic, understand that your edits haven’t necessarily vanished into thin air—they’re likely just separated from the image file.

The most common culprit is a missing sidecar file. If you’ve moved, renamed, or deleted the XMP file without its corresponding image, your editing software can’t locate those adjustment instructions. Similarly, if you’ve renamed the image file but not the sidecar, they’ll no longer be linked. Some photographers accidentally filter out XMP files when transferring photos between drives, leaving edits orphaned.

Another scenario involves catalog-only storage. Applications like Lightroom can store edits exclusively in their internal catalog rather than writing them to sidecar files. If you open that same image in a different program or on another computer without the catalog, those edits won’t appear.

To diagnose the issue, check whether XMP files exist alongside your images. Look in the same folder and verify the filenames match exactly. If sidecars are missing but you have catalog backups, you can often export or write the metadata back out. Enable “Automatically write changes into XMP” in your software settings to prevent future disappearances. For lost edits without backups, unfortunately recovery isn’t possible—making preventive measures essential.

Moving Files Between Computers or Drives

Here’s the harsh reality: you can lose hours of editing work in seconds if sidecar files don’t follow their RAW companions during transfers. Think of it like this—when you move a photo from your memory card to your computer, or between drives, you’re moving a family unit that needs to stay together.

The most common mistake? Using simple drag-and-drop operations that only grab the RAW files while leaving sidecars behind. This happens because many photographers don’t realize those XMP or other sidecar files exist in the first place. When you open your images later, all your edits have vanished.

The solution is straightforward: always use your photo organization software to handle transfers. Programs like Lightroom, Capture One, or Photo Mechanic are designed to keep families together, automatically moving sidecars alongside their RAW files.

If you’ve already separated them, don’t panic. Most editing software can reconnect orphaned sidecars. In Lightroom, for example, place the XMP files in the same folder as their corresponding RAW files, then right-click and select “Read Metadata from Files.” The software will recognize the relationship and restore your edits.

Pro tip: when backing up, always select entire folders rather than individual images to ensure nothing gets left behind.

Software Won’t Read Your Sidecar Files

You’ve probably experienced that sinking feeling when you transfer edited photos to a different computer or try opening them in another application, only to find all your adjustments have vanished. This happens because not all software speaks the same sidecar language.

Adobe’s XMP format is relatively universal, but proprietary formats like Canon’s THM or manufacturer-specific sidecar variations often won’t transfer between different editing programs. If you primarily edit in Capture One but occasionally need to work in Lightroom, you might find your edits don’t carry over seamlessly.

The workaround? Stick with one primary editing application when possible, or use software that supports XMP standards if you need flexibility. You can also export developed JPEGs or TIFFs as a backup when sharing work across platforms. Some photographers maintain two separate catalogs for different programs rather than trying to force compatibility. When collaborating with others, always communicate which software you’re using and consider sharing the original RAW files alongside any XMP sidecars to give your colleagues a clean starting point if compatibility issues arise.

Understanding sidecar files might seem like a minor technical detail, but it’s actually fundamental to protecting your creative work. Think of it this way: every edit you make, every adjustment you perfect, lives in these small companion files. When you grasp how they work and develop good management habits, you’re essentially creating a safety net for countless hours of post-processing effort.

Let’s recap the essentials. Always keep sidecar files with their corresponding RAW images—they’re a package deal. When backing up your photo library, ensure your backup system captures these files too. Check your editing software settings right now to confirm where sidecars are being saved and whether you’re using embedded metadata, XMP sidecars, or proprietary formats. Understanding your current setup is half the battle.

Before transferring files between computers or sharing them with collaborators, take a moment to verify that sidecars are coming along for the ride. This simple check can save you from the frustration of arriving at a shoot location or opening a project only to find your edits have vanished.

Here’s the good news: once you’re aware of sidecar files and how your workflow handles them, managing them becomes completely automatic. You’ll naturally develop habits that protect your work without even thinking about it. Check your software settings today, organize your backup strategy to include sidecars, and you’ll have peace of mind knowing your creative decisions are preserved alongside every image you capture.