**Postcolonial theory examines how colonial power dynamics continue shaping visual representation long after empires formally ended.** When you photograph subjects from cultures different than your own, or document communities with colonial histories, you’re navigating terrain this theory illuminates. It asks: Who has the power to represent whom? Whose stories get told, and through whose lens?

For photographers, postcolonial theory isn’t abstract academic philosophy—it’s a practical framework for ethical image-making. Consider how National Geographic’s archive reveals decades of exoticizing “primitive” cultures for Western audiences, or how travel photography often perpetuates stereotypes established during colonial rule. These patterns didn’t disappear when colonies gained independence; they embedded themselves in visual culture, influencing everything from editorial choices to Instagram aesthetics.

Understanding postcolonial theory means recognizing three critical realities in your practice. First, the camera itself carries colonial legacy—it was a tool of documentation and control in colonized territories. Second, certain photographic tropes (the “noble savage,” the “exotic other,” poverty tourism) directly descend from colonial-era imagery. Third, who gets to be photographer versus subject often mirrors historical power imbalances.

This framework doesn’t demand guilt or paralysis. Instead, it offers photographers tools for more conscious, respectful work—asking better questions before clicking the shutter, understanding historical context, and creating images that honor rather than extract from their subjects.

What Postcolonial Theory Actually Means (Without the Academic Jargon)

The Core Ideas You Need to Know

At its heart, postcolonial theory in photography examines who gets to look, who gets looked at, and who controls how stories are told through images. Let’s break down the essential concepts that’ll help you recognize these dynamics in your own work.

**The Gaze** refers to the perspective from which we photograph. When Western photographers historically documented colonial subjects, they created what’s called the “colonial gaze”—a way of seeing that positioned subjects as exotic, primitive, or inferior. Think of early 20th-century National Geographic images that presented non-Western cultures as curiosities rather than complex societies.

**Othering** happens when photography emphasizes differences to make subjects seem foreign or less human. This shows up in composition choices, like photographing people from above to diminish them, or focusing solely on poverty while ignoring a community’s dignity and complexity.

**Representation** asks: does your image reflect reality or reinforce stereotypes? When you photograph a culture not your own, are you showing nuanced humanity or clichéd tropes? For example, photographing only poverty in developing nations while ignoring middle-class life creates an incomplete, skewed narrative.

**Power dynamics** recognize that the photographer typically holds more power than the subject—you control the frame, the story, and where the image appears. Understanding this imbalance means approaching subjects as collaborators rather than simply visual material.

These concepts aren’t about guilt—they’re tools for creating more thoughtful, ethical, and honestly representative photography that honors your subjects’ full humanity.

Key Thinkers Who Shaped the Conversation

Three pivotal scholars transformed how we understand visual representation and power dynamics—insights that directly impact how photographers approach their subjects today.

**Edward Said** introduced the concept of “Orientalism” in 1978, demonstrating how Western photographers and artists created stereotypical images of the East that served colonial interests. For photographers, his work raises a crucial question: Are you documenting reality or reinforcing harmful stereotypes? Said’s ideas encourage us to examine whose perspective we’re privileging when we frame a shot.

**Homi Bhabha** developed the concept of “hybridity”—the idea that cultural identities aren’t pure or fixed but constantly blending and evolving. For visual storytellers, this means recognizing that your subjects exist in complex cultural spaces, not simple categories. His work challenges photographers to capture the nuanced, in-between spaces of identity rather than exotic “otherness.”

**Gayatri Spivak** asked the famous question “Can the subaltern speak?”—examining whether marginalized voices can truly be heard within dominant power structures. For photographers, this translates practically: Who gets to tell the story? When you photograph communities different from your own, are you amplifying their voices or speaking over them? Spivak pushes us to consider collaboration and consent as ethical imperatives, not just courtesies.

The Colonial Camera: How Photography and Empire Grew Up Together

The Ethnographic Gaze: When Cameras Became Classification Tools

During the height of colonial expansion, photography wasn’t just documenting the world—it was actively creating visual hierarchies that would shape perceptions for generations. Colonial administrators and ethnographic photographers systematically photographed indigenous peoples in ways that categorized them as specimens rather than individuals, turning the camera into a tool of classification and control.

The practice was chillingly methodical. British colonial officer J.H. Hutton’s photographs of Naga tribes in India during the 1920s exemplified this approach: subjects were posed against plain backgrounds, often stripped of context and clothing, measured with rulers visible in the frame, and photographed from standardized angles like police mugshots. These weren’t portraits celebrating humanity—they were catalog entries supporting theories of racial difference.

French colonial photographers in West Africa created elaborate “type” photographs, claiming to document distinct “racial characteristics.” The problem? These images were staged, manipulated, and interpreted through existing prejudices. A person’s value, intelligence, and social position were literally being determined by their photographic representation.

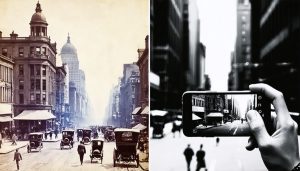

The impact extended beyond individual images. These photographs filled anthropological textbooks, museum displays, and government archives, becoming “evidence” for discriminatory policies. They created a visual language that positioned colonized peoples as primitive, exotic, or inferior—a gaze that persists in problematic ways even in contemporary travel and documentary photography.

Understanding this history helps photographers recognize how camera angles, lighting choices, and compositional decisions can either perpetuate or challenge historical power dynamics.

The ‘Exotic’ Postcard Industry and Visual Stereotypes

The picture postcard industry of the late 19th and early 20th centuries became a powerful engine for spreading colonial imagery worldwide. Commercial photographers working in colonized territories understood that European and American audiences craved “exotic” scenes—images that confirmed their preconceptions about distant lands and supposedly “primitive” peoples.

These photographers often staged photographs deliberately. They’d ask subjects to wear “traditional” clothing they might not normally wear, position them in artificial poses, or photograph them in ways that emphasized difference rather than common humanity. Studios in North Africa, for instance, mass-produced postcards of veiled women, bustling “Oriental” markets, and “native types” that bore little resemblance to everyday life but sold exceptionally well.

The commercial incentive was clear: stereotypical images sold better than authentic representations. This created a feedback loop where photographers produced what audiences expected, which in turn reinforced those expectations. These postcards weren’t just souvenirs—they were visual arguments supporting colonial narratives about cultural hierarchy and the “civilizing mission.”

The legacy persists today in travel photography. Think about how certain destinations are still photographed through distinctly colonial lenses: the “timeless” village untouched by modernity, the colorfully dressed “local” who exists primarily as visual decoration, or the poverty tourism that frames human struggle as aesthetic subject matter. When we photograph in unfamiliar places, we’re navigating terrain these early commercial photographers mapped out—often problematically. Understanding this history helps us make more conscious, respectful choices behind the camera.

Postcolonial Photography Today: What This Looks Like Behind the Viewfinder

Travel and Documentary Photography’s Ongoing Challenges

Documentary photography continues to wrestle with uncomfortable questions that postcolonial theory brings to the forefront. At its core: who has the right to tell whose story, and what power dynamics are at play when that storytelling happens?

Consider the persistent issue of poverty tourism—photographers from wealthy nations traveling to document suffering in developing countries. While intentions may be genuine, these images often reinforce stereotypes about helplessness and backwardness. The photographed subjects become objects rather than individuals with agency, their entire communities reduced to single narratives of need. This dynamic mirrors colonial-era practices where Western observers documented “exotic” cultures for consumption back home.

The “white savior” narrative presents another troubling pattern. We’ve all seen the images: a smiling Western volunteer surrounded by children in Africa or Asia, the photographer positioned as hero bringing aid or awareness. These photographs center the privileged outsider rather than local voices, perpetuating the colonial notion that communities in the Global South require outside intervention to solve their problems.

Ethical documentary practices demand that photographers ask difficult questions before pressing the shutter. Have subjects provided informed consent? Does this image respect their dignity? Am I perpetuating harmful stereotypes? Who benefits from this photograph—me, or the community I’m documenting?

These challenges aren’t insurmountable, but they require photographers to acknowledge the historical weight their cameras carry and commit to more equitable, collaborative approaches to storytelling.

Fashion, Editorial, and Commercial Work

The commercial photography industry has historically perpetuated narrow beauty standards and cultural stereotypes through model selection, styling choices, and location settings. Postcolonial theory challenges us to recognize how these decisions reflect and reinforce colonial hierarchies.

Consider fashion campaigns that consistently feature white models in “exotic” locations, positioning non-Western cultures as mere backdrops for Western consumption. This practice reduces diverse cultures to aesthetic props while maintaining Western subjects as the default standard of beauty and aspiration.

Model diversity extends beyond simply including faces of different colors. It requires genuine representation—working with models who aren’t asked to conform to Eurocentric beauty standards, compensating them fairly, and ensuring they’re not tokenized. When brands photograph Indigenous or traditional clothing, questions arise: Who benefits financially? Are cultural consultants involved? Is the context respectful or merely “trending”?

Cultural appropriation in commercial work often manifests through styling choices—bindis, traditional garments, or sacred symbols used without understanding or permission. As photographers, we must ask: Does this shoot exploit cultural elements for commercial gain? Are we perpetuating stereotypes or creating authentic, collaborative representation?

These considerations directly impact your commercial portfolio’s ethics and relevance in today’s culturally conscious market.

The Counter-Narrative: Photographers Reclaiming Their Own Stories

Today’s photographers from formerly colonized regions are actively writing back to colonial visual histories. Rather than being subjects of someone else’s lens, artists like Zanele Muholi from South Africa, Newsha Tavakolian from Iran, and Sebastião Salgado from Brazil are creating powerful work that centers their own communities’ experiences and perspectives.

These artists exemplify photographers reclaiming their stories by developing visual languages that reject Western aesthetic dominance. Muholi’s intimate portraits of Black LGBTQ+ South Africans directly challenge both colonial and post-apartheid erasure. Tavakolian documents Iranian women’s lives with complexity and nuance, countering stereotypical Western representations.

This movement of reclaiming cultural narratives isn’t about rejecting photography as a medium, but rather transforming it from a tool of colonial documentation into one of self-representation and resistance. These photographers prove that who holds the camera fundamentally shapes the story being told.

Practical Ways to Apply Postcolonial Thinking to Your Photography

Questions to Ask Before You Shoot

Before pressing the shutter, take a moment to run through this essential checklist that will help you approach your work with greater cultural awareness and ethical responsibility.

**Whose story am I telling?** Ask yourself whether you’re documenting your own community or entering someone else’s space. Are you amplifying voices that need to be heard, or are you speaking over them? The distinction matters because it affects your authority and responsibility in representing these subjects.

**What’s my relationship to these subjects?** Examine your position honestly. Are you an insider with lived experience, or an outsider looking in? Neither position is inherently problematic, but each requires different approaches to respect and representation. Outsiders need to work harder to understand context and avoid superficial interpretations.

**Have I obtained meaningful consent?** Go beyond a simple model release. Does your subject understand how and where their image will be used? Have you explained your creative intent? True consent means your subjects know what they’re agreeing to, not just signing a form they haven’t fully comprehended.

**Am I perpetuating stereotypes?** Review your planned composition and framing critically. Does it reduce people to simplistic narratives of poverty, exoticism, or victimhood? Real people deserve complex, nuanced representation that respects their full humanity.

**Who benefits from this photograph?** Consider whether your work primarily serves your portfolio and career, or whether it genuinely serves the community you’re photographing. The most ethical photography creates mutual benefit and respects the dignity of all involved.

Technical and Creative Choices That Matter

Your camera settings and creative decisions carry more weight than you might realize—they can either reinforce colonial perspectives or actively dismantle them. Let’s explore how specific technical choices shape the narrative.

**Lighting decisions** profoundly impact representation. Colonial-era photography often used harsh, flattening light that obscured the features and dignity of non-Western subjects. Today, thoughtful lighting that reveals skin tone nuances across the full spectrum challenges this legacy. Consider how Renaissance portrait lighting (often called “Rembrandt lighting”) became the default “professional” standard—a Eurocentric approach. Experimenting with alternative lighting patterns acknowledges that beauty and dignity aren’t one-size-fits-all.

**Framing and composition** also tell stories about power. Shooting from above creates a diminutive effect, while eye-level or slightly lower angles convey equality and respect. The colonial gaze frequently positioned non-Western subjects as specimens to be observed rather than individuals with agency. Compare a travel photograph where subjects are unaware and reduced to “exotic scenery” versus one where subjects engage directly with the camera, acknowledging their participation in the image-making process.

**Editing choices** matter tremendously. Over-saturating colors to emphasize “otherness” or applying filters that make environments appear uniformly impoverished perpetuates stereotypes. Conversely, editing that maintains authentic color relationships and contextual complexity respects your subjects’ lived realities. The key is asking yourself: does this creative choice serve the subject’s humanity, or does it serve my preconceptions?

Collaboration and Representation: Working With Your Subjects

Participatory photography transforms the traditional photographer-subject dynamic into a collaborative partnership. Instead of simply capturing images of people, invite your subjects into the creative process. Show them your shots as you work, discuss composition choices, and ask how they’d like to be represented. This approach is particularly crucial when documenting cultural heritage or working across cultural differences.

Consider sharing final edit approval with your subjects, especially in documentary work. While this might feel uncomfortable initially, it builds trust and prevents harm. Some photographers even provide their subjects with cameras to capture their own perspectives—a practice that often reveals insights outsiders would miss entirely.

Remember that consent goes beyond a signed form. Discuss how images will be used, where they’ll appear, and who benefits from their publication. If you’re profiting from photographs of marginalized communities, consider how you might share those benefits or amplify your subjects’ voices through your platform. This ethical approach creates more authentic, respectful work while challenging photography’s colonial legacy.

Real-World Examples: Analyzing Images Through a Postcolonial Lens

Let’s examine how postcolonial theory translates from concept to practice by analyzing actual images and photographic approaches.

**Case Study 1: The “Exotic Other” in Travel Photography**

Consider the classic problematic image: a Western photographer capturing Indigenous children in “traditional” dress, posed against a picturesque but poverty-stricken background. These images often strip subjects of context, present them as timeless relics rather than contemporary people, and reinforce the photographer’s position as observer of the “exotic.” The subjects rarely have agency in how they’re portrayed.

Now contrast this with contemporary approaches where photographers collaborate with communities, share creative control, and include subjects’ own narratives. When Kenyan photographer Tahir Carl Karmali documents his own community, the resulting images carry inherent authenticity—people appear as complex individuals rather than visual symbols of difference.

**Case Study 2: National Geographic’s Evolution**

National Geographic’s 2018 acknowledgment of its racist past provides valuable lessons. Historical issues featured images that portrayed non-Western peoples as primitive curiosities for Western audiences. Women were often photographed bare-breasted while Western women never were, creating a dehumanizing double standard.

Their more recent work demonstrates thoughtful alternatives: naming photographers from the regions being documented, including photo credits for local collaborators, and commissioning work from photographers engaged in diaspora storytelling who bring insider perspectives to their subjects.

**Case Study 3: Fashion and Editorial Photography**

Problematic patterns persist when fashion photography uses non-Western settings as mere backdrops—think luxury brands shooting among “exotic” locals who become props. Ethical alternatives include hiring local crews, compensating all people who appear in images, and questioning whether you’re photographing *with* a community or simply *in* their space.

**Recognizing Colonial Patterns**

Ask yourself: Does this image present people as decorative elements? Does it imply the photographer has special access to “authentic” experiences unavailable to subjects themselves? Are power dynamics visible—who’s looking, and who’s being looked at?

The goal isn’t avoiding cultural documentation entirely, but rather approaching it with humility, collaboration, and genuine interest in subjects as equals rather than objects of fascination.

Understanding postcolonial theory doesn’t mean second-guessing every creative decision or feeling guilty about your work. Instead, it’s about expanding your perspective to create photographs that are richer, more authentic, and more respectful of both your subjects and your audience.

When you approach photography with awareness of power dynamics, cultural context, and historical representation, you naturally develop stronger relationships with your subjects. You ask better questions, listen more carefully, and capture moments that tell fuller truths. Your images become more nuanced because you’re seeing beyond stereotypes and surface-level aesthetics.

This isn’t about censorship or walking on eggshells—it’s about thoughtful craftsmanship. Just as you’ve learned to master light, composition, and timing, understanding postcolonial theory adds another dimension to your creative toolkit. It helps you recognize when you’re unconsciously perpetuating tired tropes and empowers you to make intentional choices instead.

The best part? This journey doesn’t end here. Postcolonial theory continues evolving as our world changes, and your practice can grow alongside it. Keep reading, listening to diverse voices, examining your own work critically, and staying curious. Your photography—and the communities you photograph—will be better for it.